Abandoning HS2 Phase 2b: A disaster that most don’t realise

What does the Government mantra of ‘levelling up’ actually mean? A quick google search suggests I’m not the only one who’s curious as to what the definition is, which areas it applies to, or what success looks like.

CGI of future HS2 service

What we do know is that a White Paper on this very subject will be published imminently. Led by the Prime Minister and presumably curated from his second home at Peppa Pig World, it intends to focus on challenges including “improving living standards, growing the private sector and increasing and spreading opportunity.”

This appears to fit with a quickly realised consensus amongst academics and industry, who’ve arrived at a view that to level up is to reduce inequality between places while improving outcomes in all places. In economic policy terms, one of the critical success factors is the quality of infrastructure to support high-value jobs and to allow people to enjoy great lives.

In an era of required decarbonisation, this approach must include a move to higher quality, higher capacity mass transit including rail. Brilliantly however, the Government has already punctured a hole in this particular balloon by cancelling the Eastern leg of its planned HS2 rail scheme, depriving large parts of the North of the rail capacity it badly needs to increase its economic competitiveness. This blog entry examines why this is an act of economic self-harm and suggests what the Government ought to do next to get its levelling up plans back on-track. (Apologies for the pun)

The real purpose of HS2: increasing rail capacity to deliver myriad benefits

One of the main bugbears I continue to have about HS2 is its name, which does not reflect its purpose at all – to build capacity within a network already under severe constraints and as a key pillar of the decarbonisation of transport. This erroneous naming has skewed public debate towards improvements in inter-city journey times (“Why should the Government spend £100bn for me to get to London 20 minutes early?” etc) rather than how its operation will lead to more regular and reliable commuter services across the network and open up freight lines to improve the efficiency of industry.

HS2 as previously planned (July 2017)

At its most basic level, the new high-speed railway between London, the Midlands and (now) the North West will be constructed as a separate line. It will be dedicated only to high-speed passenger trains. As a result, HS2 will create additional opportunities for increasing freight and commuter traffic on three Britain’s important mainlines. One of them is the West Coast Main Line, which is considered to be the busiest mixed-use railway in Europe given it runs at full capacity and has no possibility to serve new more passenger and freight trains. HS2’s construction and operations unblocks this line, the Midland mainline and the East Coast mainline – though as this blog will point out, last week’s announcement removed a large part of the capacity improvements for the latter two lines.

So how will this capacity increase manifest itself in real life?

– HS2 will free some capacity for regional and commuter trains that make far more stops than the high-speed ones, thus improving commuter connectivity away from the HS2 line itself and supporting passenger modal shift away from the car.

– It will also free up more freight trains being run. It’s worth keeping in mind that one utilised freight train is the equivalent of removing up to 76 lorries from Britain’s roads, thereby speeding up deliveries and improving air quality.

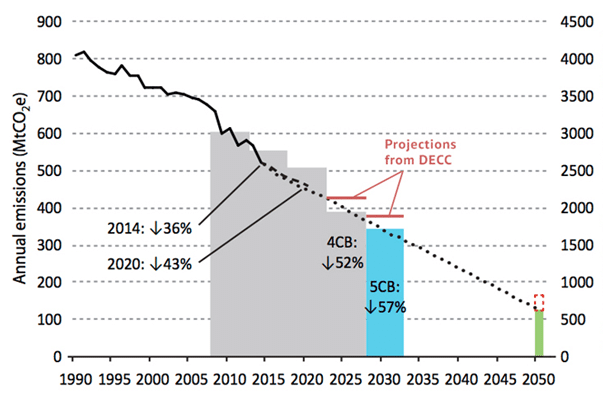

The predicted overall impact of the original scheme was therefore significant. HS2 Ltd itself estimated that carbon emissions from HS2 would be seven times less than passenger cars and 17 times less than domestic air travel. Travelling 500 miles on HS2 was predicted to use the same amount of carbon as 70 miles in a car and just 29 miles by plane. Most crucially of all, the capacity ‘released’ by HS2 was projected to carry 2.5 million lorries worth of cargo each year while producing 76% less carbon emissions than by road.

HS2’s configuration was by no means perfect, with a number of calls for better integration with existing or planned regional services including Northern Powerhouse Rail; similarly, you could argue that its planned operation date of 2033 (before recent announcements!) was nowhere near aggressive enough to fully support the UK’s target of reducing its carbon emissions by 68% by 2030 (versus a 1990 baseline). It did however provide a feasible, evidenced plan to improve capacity, economic competitiveness and modal shift. (If you do want to read some well-researched suggested improvements for HS2 to account for, read Railfuture’s report here).

Grant Shapps announces the IRP, 18 November 2021

The Government’s publication of the Integrated Rail Plan (IRP) last week however signalled the death knell to these projected improvements through the cancellation of Phase 2b of the route to Leeds – acting as a brake to levelling up even before the white paper is published. Why?

The IRP torpedoes this approach

The IRP brings together a series of existing spending commitments and a small number of new ones into a single framework for future public investment, totalling some £96bn. That phrase ‘levelling up’ creeps in again during the Prime Minister’s foreword, in claiming what the IRP will deliver:

“I am proud to present the Integrated Rail Plan. The biggest ever government investment in our rail network, in redressing decades of underspending in the Midlands and North, and in levelling up our country.

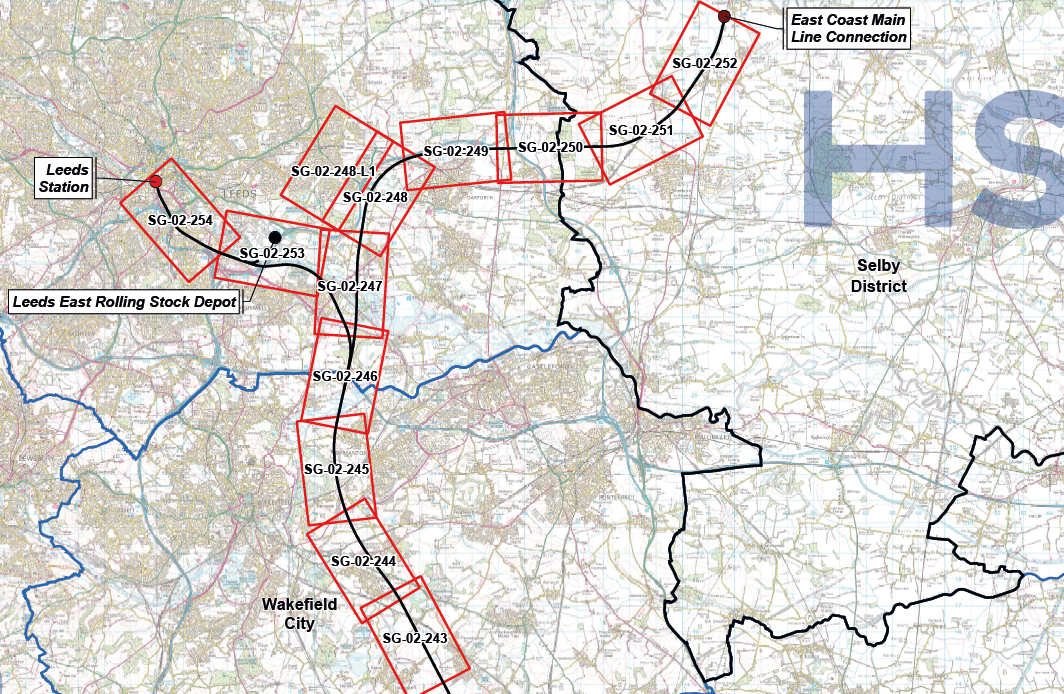

Safeguarded land for HS2 in West Yorkshire (January 2021 map)

It builds three new high speed lines, totalling around 110 miles of route and transforming connections to, from and between the East and West Midlands, the North West, Yorkshire, the North East, Scotland and North Wales. One of these will be Northern Powerhouse Rail, keeping my promise to build it between Leeds and Manchester.

But we will go further, extending NPR to Liverpool, York, the Tees Valley and Newcastle. It fully electrifies, modernises and upgrades two existing diesel main lines, the Midland Main Line from London to Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield and the Transpennine Route, from Liverpool to Manchester, Leeds and York. This completes the electrification of around 180 route miles and more than 75% of Britain’s main trunk routes.”

UK emissions – glidepath to net-zero 2050

As ever though, a plan is just as much about what won’t be delivered as what will….and away from the hyperbole, the hammer blow of cancelling the full eastern leg of HS2 Phase 2b is confirmed later in the document – with the line terminating at East Midlands Parkway instead. In a double blow for the North, the claim of ‘extending NPR’ is actually a huge scaling back of a previous promise to build Northern Powerhouse Rail in full – meaning new lines will no longer built between Liverpool and HS2 (into Manchester) and Manchester and Leeds.

In justifying this decision, absolutely no reference to its effect on capacity is referenced, instead focusing on the line’s proximity to cities in the Midlands……

“As Doug Oakervee, the reviewer of HS2, found, the previous plans were designed largely in isolation from the rest of the transport network. They would have spent billions of pounds on a new rail link to the East Midlands that didn’t directly serve any of the region’s three main cities.

TfN’s preferred option for Northern Powerhouse Rail would also have seen us spend billions upgrading the conventional line between Leeds and Manchester – and then tens of billions more, straight afterwards, building a second line between the same two places. Under those plans, many places on the existing main lines, such as Doncaster, Huddersfield, Wakefield and Leicester, would have seen little improvement or a worsening in their services.

The fastest services to the East Midlands would have been concentrated on a parkway stop. Losing the convenience of city-centre stations, good connections to existing local public transport networks, and proximity to thousands of shops and businesses. There was nothing directly for wider improvements to local transport.”

An act of long-term harm

This justification is curious to say the least and misses the enormous knock-on negative effect of such a swingeing decision. In short:

– With HS2 now being built from London to Birmingham and Birmingham to Manchester (in two parts bisecting at Crewe), the line is in effect now acting as a bypass for the West Coast Main Line.

– In not building HS2 Phase 2b to Leeds, the scheme loses the East Midlands Hub at Toton – crucial to regional connectivity improvements – and decimates capacity for stopping services on the Midland Main Line, given “HS2 trains will continue directly to Nottingham, Derby, Chesterfield, and Sheffield on the upgraded and electrified Midland Main Line”.

– With no high speed service to Leeds, there is no relief for the East Coast Main Line or for regional stopping services serving it.

– Passengers in the Midlands and the North will therefore endure the double negative of a high speed line removal to major cities and fewer local passenger stopping services at a time when the need for modal shift is becoming ever more acute. Freight operators in the North and the Midlands who want to bring goods in via rail to make efficiency and carbon savings also hugely lose out.

Make no mistake – the IRP signals a clear reduction in planned rail spend, with its overall ‘£96bn’ spend (with most on existing projects) representing a scaling back of ambition and future rail capacity. It is impossible to reconcile this position with either the Government’s levelling up ambition or its medium or long-term carbon reduction targets, two of its supposed priorities.

A second headache

A further kick in the teeth for the North and the Midlands came in the IRP’s treatment of land already safeguarded for the now cancelled HS2 Phase 2b. Page 17 of the document commits the Government to a vaguely worded options appraisal (with no funding commitments) on future high speed rail services to Leeds, resulting in land already blighted or safeguarded by the now cancelled route remaining with that legal status:

“(We will) look at options on how best to take HS2 services to Leeds. Safeguarding of the previously proposed high speed route north of East Midlands Parkway will remain in place pending conclusion of this work.”

Huge amounts of good quality, developable land is currently blighted by the route, including consented land earmarked in the East Midlands and Yorkshire for primarily Manufacturing and Logistics development. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, this land is highly sought after with a resulting squeeze in supply.

The Government’s decision to retain safeguarding status is a classic case of having your cake and eating it. It prevents any of this land being brought forward for commercial development unimpeded, acting as a further brake on regional growth and undermining any arguments of further levelling up, whilst not providing a hint of a long-stop date for the completion of the options work. It leaves affected land developers utterly in the dark as to what happens next.

So what should the Government do next?

In an ideal world, the Government would perform a volte-face and commit to funding and building Northern Powerhouse Rail (the high-speed east-west link) in full, HS2 Phase 2b East in full and to fully electrify the existing Transpennine Route as a clear sign of levelling up and decarbonising how people travel and how goods are distributed. Whilst some may baulk at the idea of tens of billions being spent on these projects, the economic and social prize at stake is abundantly clear and in my view few other planned infrastructure programmes offer the level of benefit that this tripartite programme would.

I am however a realist and given recent headlines suggest that the Prime Minister’s white paper on Levelling Up will have no new money attached to it, the main weapon in the Government’s armoury is to get on with its existing plan without any further delay or excuse. This means:

– Building all planned phases of HS2 in line with timetable to relieve the considerable pressure on the West Coast Mainline as an absolute priority.

– Working cheek by jowl with regional leaders, including elected City Region Mayors, to get on with the truncated versions of Northern Powerhouse Rail and the HS2 link to East Midlands Parkway and to listen to their representations in adjusting routes or boosting public transport links to these new routes.

– Getting on with completing the options appraisal for future high speed lines (or alternatives!!) to Leeds in the next 12 to 18 months, immediately committing to the recommended option and the land required, and subsequently de-safeguarding land no longer required.

I wholeheartedly agree with Leeds City Council’s recent call ‘for an urgent review of the safeguarded land to bring greater certainty around future development’ and you can read more on the Council’s ambitions here.

Listen to the experts

This blog is merely an introduction to HS2 and I hope it serves as a catalyst for readers to look in further detail at both the programme and in future rail investment in the UK and across the world. There are three people in the rail industry who I recommended listening to on both HS2 and the future of rail to support sustainable growth.

Gareth Dennis is a rail engineer with a genuinely infectious enthusiasm for all things rail, often perambulating round the network to inform his work on the #railnatter podcast. I highly recommend following him at https://twitter.com/GarethDennis or listening to the aforementioned podcast as it’s genuinely insightful.

Nigel Harris is Editor of Rail magazine who helpfully explained (to any mainstream media outlet that would listen) why the cancellation of Phase 2b was such bad news for industry. You can listen to his interview with GB News here and follow him at https://twitter.com/RAIL.

Nick Gallop is an independent rail consultant who has a fairly encyclopaedic knowledge of the UK and European rail freight networks, with a particular interest in developing inland ports to accelerate the move from road to rail-based logistics. Follow Nick at https://twitter.com/IntermodalityUK.